The Legacy of Martinican Women in French Politics

On June 30, 2017, the world learnt of the death of Simone Veil, architect of the French law legalizing abortion, and an advocate for women’s rights and equality. The subsequent period of national mourning and paying tribute has been the occasion for much public reflection on Veil’s contributions to the advancement of women in public office in France. Notably, in the 1970s when Veil argued for the legalization of abortion in the National Assembly, only about eight women held seats in the French parliament. Today that number is 223.

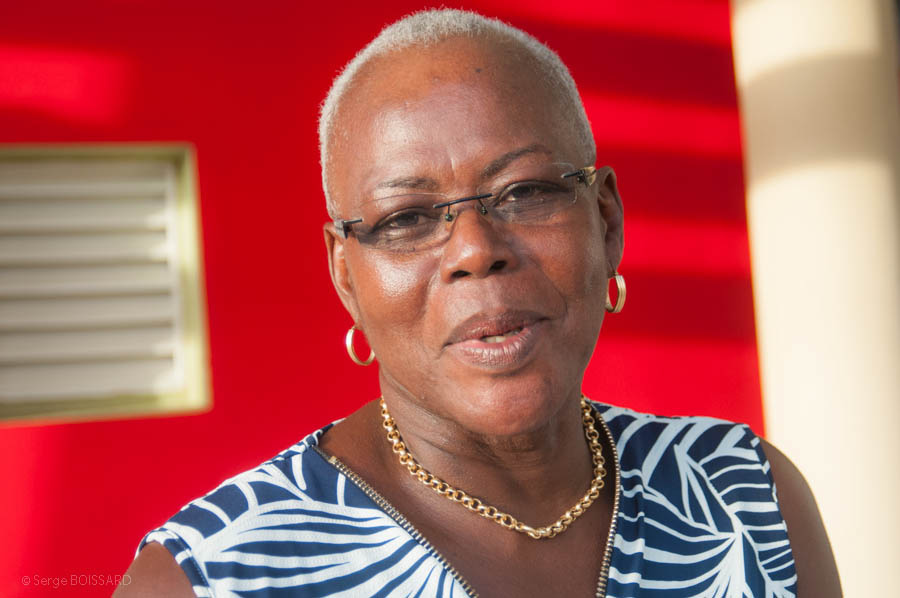

This public conversation on the obstacles faced and victories won by French women in the political sphere, comes on the heels of the historic June 18, 2017 election of Josette Manin, the first woman parliamentarian to represent the overseas department Martinique in the National Assembly.

Manin’s election is historic because it interrupts the long streak of Martinican men elected to some of the highest positions in the French government. Manin is not new to male-dominated spaces. She made the transition from the world of professional sports as a handball player, to the political sphere as a municipal councilor and later the first woman president of the Conseil Général. Her election has been heralded as a manifestation of Martinique’s desire for a radical change in its political landscape, an advancement that seems long overdue given that since 1945, the neighboring island of Guadeloupe has been represented in the French parliament by women deputies including Eugénie Eboué, Gerty Archimède, Albertine Baclet and Lucette Michaux-Chevry.

It would be easy, therefore, to dismiss Martinique as simply behind the curve, a late adopter of a feminist legacy of advancing the representation of women in government that a political figure like Veil represented. However, taking a historical view of the diverse ways in which Martinican women have been vocal and active participants in politics allows us to consider a wider range of political action and representation beyond the singular statistic of the number of elected representatives. Indeed, in the mid-20th century, at the pivotal moment when Martinique became an overseas department of France, women were key players in the island’s transition from a colony of subjects to a department of citizens. Paulette Nardal was one of these women.

Born on October 12, 1896 in François, Martinique, Nardal moved to Paris in 1920 to study English literature at the Sorbonne. Her publications in journals like La Depêche africaine and La Revue du monde noir, which she co-founded in 1931, articulated a collective black diasporic identity. Today, Nardal is best known for her significant contributions to black transnationalism and the conversation on race and place in France in the interwar years. However, her work extended well beyond the sphere of 1920s Black Paris. After nearly two decades living and working in France, Nardal returned to settle permanently in Martinique under traumatic circumstances. In September 1939, she boarded the SS Bretagne, the ship on which the well-known Martinican intellectuals Aimé and Suzanne Césaire had traveled on their return to Martinique from Paris. Traveling in the opposite direction back to Paris after a short work-related stay in Martinique, Nardal experienced firsthand the violence of World War II when the ship was torpedoed by German submarines and sank off the English coast. Nardal was rescued, but the ordeal left her with a permanent limp.

After nearly a year in hospital, she chose to return, not to Paris but to Martinique where she taught English to dissidents preparing to travel to Dominica to join the French Resistance. In 1944, she founded the Rassemblement féminin (Feminine Rally), the Martinican branch of the moderate, Catholic French women’s organization Union féminine civique et sociale (Civic and Social Feminine Union). She also served as editor of the Feminine Rally’s journal La Femme dans la cité (Woman in the City) published monthly between 1945 and 1951.

Nardal’s editorials in Woman in the City came at an important time in Martinique’s history. With the passage of women’s suffrage in France in 1944 and the law of departmentalization in 1946, women in the overseas departments were precisely the demographic most impacted by these changes. Martinican women were to vote for the very first time in the decisive elections that would usher in the French Fourth Republic. Nardal therefore saw Woman in the City as an important platform from which to engage in pertinent and sometimes controversial conversations about the role that Martinican women would play as first-time voters and newly-recognized citizens of France.

Nardal believed that women’s political action should permeate all aspects of public life. She evoked memories of the just-ended World War to stress Martinican women’s role in postwar rebuilding efforts. She argued that women, by becoming full citizens and participating actively in political life, would be the ones to reconstruct the war-ravaged nation. As she wrote in the pages of Woman in the City, Martinican women had entered the city to rebuild it.

For Nardal, Martinican women’s work in the public domain was to be both local and international in scope. In her editorial “Martinican Women and Politics,” written four months after departmentalization was voted into law, she issued one of her most urgent calls to this effect: “Martinique should draw attention to itself through the importance of female participation in decisive elections. We must present the true face of Martinique, this time, to France and to the world.” Through defining their political interests, Antillean women would be engaged in a collective project of self-definition. Nardal therefore urged her readers to become informed voters: “In order to better clarify our choice, we thus have the duty to inform ourselves about social questions and involve ourselves in deep reflection based on knowledge of ourselves and observations of reality.” She argued that Martinican women’s political action went beyond the single act of casting a vote. It also involved a collective self-consciousness, cultivated by observing and gaining knowledge of the social realities on the island. Consequently, she saw women’s increased presence on the political stage as a social and psychological revolution. Nardal imagined, in 1945, the kind of disruption and overhaul of Martinique’s political structure that commentators today hope to find in Josette Manin’s election.

The many contributors to Woman in the City were hopeful that Martinican women would be an important force in local and international politics. Nardal embodied this hope in 1946 when she was appointed to the United Nations as an area specialist for the French West Indies. However, she also experienced firsthand the obstacles that many women faced in their work in visible positions of political influence. For example, in its December 21, 1946 coverage of her appointment to the U.N. position, the Chicago Defender’s headline described the 50-year-old Nardal as “Martinique Girl Given High Post With UN Body.” The language that characterized media coverage of Nardal’s work in the mid-twentieth century is very different from the comparatively more laudatory reception of Josette Manin’s election today. Of course, for Manin there remain obstacles to recognition and equal treatment of black French women in the political arena. Remembering Nardal and the work of the Feminine Rally may therefore be a useful reminder that Martinican women across the political spectrum have historically been a formidable force and remain engaged participants in French and Antillean politics.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.