Seriously – boardgames? Yes, seriously.

A scholar of African American history comes out as a tabletop gamer.

I have a secret I want to share: I play board games, religiously. No, not Sorry and Clue and the like. Not even games like Risk. I’m talking about a new generation of strategy games that have been called Eurogames, German games, designer games, etc. Familiar titles such as Carcassonne and Ticket to Ride are “gateway” games to an amazing, expanding universe of tabletop fun.

Why am I sharing with you anything about my hobbies? Because in unavoidable ways, my pastime intersects with my scholarship, and I can no longer put off a formal reckoning of the two. What follows are some preliminary thoughts on a much larger subject – too long, I’m afraid, but necessary to establish a basis for further conversations on this.

Why am I sharing with you anything about my hobbies? Because in unavoidable ways, my pastime intersects with my scholarship, and I can no longer put off a formal reckoning of the two. What follows are some preliminary thoughts on a much larger subject – too long, I’m afraid, but necessary to establish a basis for further conversations on this.

Here’s a little table of contents:

Background

The problem with boardgame conventions

Classical archeology

Slavery in games

Recent examples

The Confederate flag

Conclusion

For those who have no idea what I’m talking about, let me start with a brief overview. The new tabletop-game craze arose in the 1990s. Gamers of my generation (born in the ‘60s) grew up on wargames (Avalon Hill, SPI), role-playing games (TSR), and wayward brands that remain unknown to most Americans (Battleline, Eon Games, Metagaming). We lived in a pocket of nerd-dom that rarely attracted attention, unless it was to blame Dungeons and Dragons for corrupting the youth and turning them into Satanists. On long weekends and over summers, we simulated Stalingrad or plotted the fall of Rome.

After college, most of us dropped it. Jobs, spouses, and kids made it impracticable to convert the basement into the hills of Pennsylvania for a never-ending recreation of Pickett’s Charge. And as the little ones got older, hauling out our old intricate simulations of Stalingrad didn’t always seem like quite the right way to bond.

Then along came the German games, a new generation of board games that offered something for the whole family. Settlers of Catan is probably the best-known of these. The game required only a quick evening rather than a days-long marathon. Additionally, it favored elegant gameplay that could be learned quickly and could engage intellects at all levels. The older military simulations (think Advanced Squad Leader) could take months if not years to learn fully, while simple children’s games bored parents silly. Finally, these games were designed to keep all players in; unlike Monopoly, no one would be eliminated until the game was over.

Here were games truly for the entire family. A whole new generation of game-playing emerged, built on an educated and moneyed consumer base with an insatiable taste for new gaming experiences, and a desire to socialize the next generation to the hobby. They were the perfect family alternative to the atomizing computer. At the same time, computers vastly enhanced the market by connecting gamers through, for example, the remarkable online community called Boardgamegeek (or “BGG,” a resource I will link to liberally below).

Significantly, the Eurogame explosion of the 1990s entirely changed boardgames’ themes. By “theme” I mean a game’s central metaphor, or ostensible subject of simulation — in short, what the game says it is about (in Monopoly, for instance, the game is about buying and trading real estate). This is in contrast to “mechanics,” which are the actual rules of a game (in Monopoly, a central mechanic is “roll and move”). Themes of war took a seat in the wayback. (It’s no surprise that the first and best of these new games emerged in Germany, a place unlikely to champion martial themes in entertainment products.) Out were battles and military conflict. Newly ascendant were trains, farms, medieval towns and cathedrals, and desert caravans. Catan, a fantasy world based on a vaguely medieval harvest and trading system, offers an excellent case in point.[1]

The problem with boardgame conventions

So the new Eurogames built their appeal on eliding military simulations and direct conflict. And yet, I want to suggest, these games have not entirely withstood some troubling representations, as I will shortly demonstrate. I am asking why this is. That is, how I should understand troubling cultural representations in my most favoritist thing to do outside of work?

We are living in a golden age of tabletop games. Literally thousands of new game designs are being published every year, and they represent a remarkable (and little-appreciated) instance of DIY technological growth. With so much new product competing for consumers’ attention, innovation is a priority. Boardgame designers are thus fierce intertextualists, building new work off of earlier mechanics the ways contemporary hip-hop artists sample and riff off of old tunes to make new ones. The result is a host of clever and ever more elegant game mechanics, which seek to increase strategic challenges while keeping playing concepts accessible and the games themselves replayable. No one just rolls dice and moves their mice anymore.

But all this inter-textuality creates strong conventions. After all, innovation on every front ceases to be intelligible to broad consumer audiences (think of artistic geniuses who were mis-understood in their day because they moved too far and too fast for contemporary tastes). Nothing more clearly emblematizes this more than the (now, thankfully, passing) propensity of many classic Eurogames to come in boxes with a medieval or early modern theme and some kind of historic-looking dude on the cover.

Likewise, many game mechanics are shared across games. In the same way that modern electronica and hip hop rely on heavily sampled breakbeats to anchor pieces that innovate on top of them, modern boardgames incorporate well-worn elements of game play (set collection, tile placement, auctions) as the bases for their clever innovations. Regular game players may quickly pick appreciate interesting new games because elements of them are familiar.

Likewise, many game mechanics are shared across games. In the same way that modern electronica and hip hop rely on heavily sampled breakbeats to anchor pieces that innovate on top of them, modern boardgames incorporate well-worn elements of game play (set collection, tile placement, auctions) as the bases for their clever innovations. Regular game players may quickly pick appreciate interesting new games because elements of them are familiar.

Boardgames are also conventional in terms of themes. For Euros, innovative mechanics usually support vintage historical themes. (Zombies and pirates tend to dominate many American games, while penguins have curiously taken over children’s games.) Because they seek to recall the face-to-face family gaming experiences of the time before computers took over our lives, tabletop games often concern topics that are similarly nostalgic, recalling not just Victorian social experiences, but often Victorian values as well. The problem for the game-playing scholar of African American history is that some of these themes seem to embrace troublesome depictions of the past.

Let’s take a light example: classical archeology. Off the top of my head, I can think of at least three games that pose players as archeologists bent on discovering ancient treasures in the Mediterranean world: Pergamon, Mykerinos, and Thebes (see Tikal or Incan Gold if you want to go to the Americas). The theme seems safe enough, at least compared with the overt militarization embodied in earlier games, and fits well with the notion of sitting down with family and friends for some old-fashioned fun. Of course, what is actually being simulated is the process by which European imperialists denuded the colonized world of its material history. Yet while they offer thoughtful and enjoyable play experiences, these games themselves raise no critical questions about the ethical issues raised by their subjects. Their purpose isn’t to trouble their themes, but to offer benign experiences in face-to-face socializing and friendly competition.

It’s important to note that gameplay rather than simulation drives these games. The theme is often little more than a plausible “skin” for what is largely an abstract game. This means that designers and publishers have many choices in how they present their product. A simulation of D-Day requires a lot of very grisly combat on beaches, but when a game is really about an interesting new worker-placement mechanic, you have a lot of leeway over how you theme it. Publishers make thoughtful, conscious decisions about this, based frequently on market considerations. When the publisher of the tremendously popular card-drafting game Dominion bought the design, it consciously chose a medieval theme over a science fiction theme to avoiding competing with a similar product.[2] The three archeology games mentioned above are really about collecting; they could be themed around, for example, an alien race bent on discovering ancient artifacts of another alien race, or collecting modern art.

It’s important to note that gameplay rather than simulation drives these games. The theme is often little more than a plausible “skin” for what is largely an abstract game. This means that designers and publishers have many choices in how they present their product. A simulation of D-Day requires a lot of very grisly combat on beaches, but when a game is really about an interesting new worker-placement mechanic, you have a lot of leeway over how you theme it. Publishers make thoughtful, conscious decisions about this, based frequently on market considerations. When the publisher of the tremendously popular card-drafting game Dominion bought the design, it consciously chose a medieval theme over a science fiction theme to avoiding competing with a similar product.[2] The three archeology games mentioned above are really about collecting; they could be themed around, for example, an alien race bent on discovering ancient artifacts of another alien race, or collecting modern art.

Now I have no desire to rain on everybody’s parade, much less to censor anything. I do not believe that a trace of malice entered anyone’s mind in developing the games I mention above, and I enjoy all three for both game play and theme. I do not believe that playing a nineteenth-century archeologist is innately “racist” or particularly harmful, as I’m pretty confident that players can separate themselves from roles they assume in games. And I absolutely bristle at the reductionist orthodoxy that, for example, leads concerned parents to demand the removal of Huckleberry Finn from high-school reading lists. My point is emphatically not to replicate the exercise here.

But games are becoming an important component of our social lives, and they tend to be played by people who consider themselves thoughtful and socially responsible. Just like any other form of entertainment media, they teach young people, and they reflect our values. It will no more do to say “it’s only a game” than it does to say “it’s only a film.” Cultural criticism is about nothing if not examining how entertainment informs our public dialogues on important matters such as race.

Undertaking this task for boardgames is far too monumental for a forum such as this. For now, let’s consider another illustrative instance: Puerto Rico, one of the most famous and important games of the last twenty years. The brainchild of a great designer (Andreas Seyfarth), it has won innumerable awards, sat near the top of the Boardgamegeek rankings for years, and has spawned a host of imitators and epigones. Players assume the role of colonial overlords on the island of Puerto Rico, presumably (though abstractly) from the beginning of its settlement. They compete to develop plantations that produce raw goods, which are then either shipped off to Europe for victory points, or converted into cash which is used to buy buildings that increase the efficiency of one’s plantations.

As a game, it’s a classic. As history, like many Euros, it leaves much to be desired. For example, tobacco, which the island never produced in quantity until the twentieth century, is far more valuable than the sugar that drove its economy for over a century. And one searches the scholarship in vain for evidence that the island ever produced indigo in quantity. Worst of all, though, the game requires “colonists” – in the form of small brown tokens – to be imported to occupy the plantations and buildings necessary to produce. One has a hard time imagining these workers to be of the Priscilla Mullins settler variety; historically, they could only be African slaves.

The point here is not to censure the game, for its point was never to teach anyone the real history of Puerto Rico, or engage in moral discussions over the slavery. Rather, I merely wish to mark the interesting cultural space it occupies. How strange that a medium (Eurogames) that developed around “peaceful” themes wound up representing slavery so obtusely. Perhaps the narrow niche that modern boardgaming occupies has insulated it from the kinds of searing cultural criticisms impossible to avoid in, say, feature films with historical themes. Perhaps the community of gamers, who tend to be highly educated, assume (as, frankly, I do) that they can enjoy their gaming experiences without succumbing to the latent influence of white supremacy.

The point here is not to censure the game, for its point was never to teach anyone the real history of Puerto Rico, or engage in moral discussions over the slavery. Rather, I merely wish to mark the interesting cultural space it occupies. How strange that a medium (Eurogames) that developed around “peaceful” themes wound up representing slavery so obtusely. Perhaps the narrow niche that modern boardgaming occupies has insulated it from the kinds of searing cultural criticisms impossible to avoid in, say, feature films with historical themes. Perhaps the community of gamers, who tend to be highly educated, assume (as, frankly, I do) that they can enjoy their gaming experiences without succumbing to the latent influence of white supremacy.

To be fair, the questions I’m raising here have long been topics of conversation within the community of gamers. The forums on boardgamegeek are rife with such discussions (check out this one, which discusses the complete neglect of slavery in Age of Empires III: The Age of Discovery). Indeed, the intense inter-textuality that characterizes boardgame design as a whole is evident in ongoing questions regarding the presentation of slavery in games. Puerto Rico may have missed it, but followers did not. Some games built on the expansion theme, such as Endeavor, treat slavery as a game element with benefits and pitfalls that players must weigh (using slaves might provide short-term benefits, but those slaves may revolt, or slavery might be abolished). Struggle of Empires takes this further, so fully incorporating slavery into its model of imperial expansion that one player thoughtfully reflected that in playing it he has “been part of countless virtual atrocities.” Other games, such as the more broadly themed Archipelago, avoid slaves altogether, but permit you to recruit native workers who may get angry and eventually revolt – a game-ending scenario. (Interestingly, the game makes no distinction between revolting native workers and a full-blown move for independence; they are considered the same.)

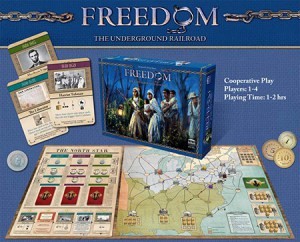

As boardgames move steadily toward the mainstream, the attention they draw has led publishers into increasingly deep considerations of the difficult issue of presenting slavery in games with historical themes. Freedom: The Underground Railroad, tackles the issue head on. Rather than asking players to identify with those who might enslave, the game asks you to take on the role of abolitionists helping fugitive slaves achieve their liberty. Interestingly, play is cooperative, meaning that players work together against the system rather than each other. (Shameless plug here: similarly inspired, I designed an online simulation, entitled Flight to Freedom, of the fugitive slave experience with the aid of my institution.)

Still, it’s not as if the problem has been solved, or any consensus has emerged. A more troubled recent case involves the popular game Five Tribes, in which players vie for control of a mythical sultanate by enlisting the aid of assassins, elders, builders, merchants, and viziers. True to its medieval Arabic theme, the game initially included a special commodity card for slaves, who can be used to aid construction projects and perform other useful functions.

Still, it’s not as if the problem has been solved, or any consensus has emerged. A more troubled recent case involves the popular game Five Tribes, in which players vie for control of a mythical sultanate by enlisting the aid of assassins, elders, builders, merchants, and viziers. True to its medieval Arabic theme, the game initially included a special commodity card for slaves, who can be used to aid construction projects and perform other useful functions.

The choice was conscious. Days of Wonder, the game’s publisher, later explained that

glossing over the historical fact that there were slaves in Persia in the 10th century felt like we were ignoring the realities of the world that Five Tribes takes place in. Calling them servants would have been the safer and politically correct decision, but in that time and place, nearly all servants were slaves. We felt that we wanted to stay true to the historical theme of the game.

As soon as the game was released concerns arose about the presence of these cards, which made many players uncomfortable. Finally, DoW succumbed to pressure, and replaced the slaves with “fakirs,” who perform the same function. The publisher explained its decision thusly:

As we already explained very clearly in the past, we did not intend to harm anyone when we included slave cards in Five Tribes. (They were in the game from the very beginning.) Despite being part of the Arabian Nights tales folklore, we do regard slavery as an important matter and condemn it.

Still, we understood that this very precise element was preventing some people from fully enjoying Five Tribes. As a publisher, we thought it was important to offer the same joyful game experience to everyone. That is why slave cards have been replaced by fakir cards in the new reprint of the game. While the name and illustration are different, the purpose of the card in the game remain the same. We sincerely hope that you will enjoy these new fakirs, as they will be precious allies to summon powerful djinns and help your builders and assassins in completing their more or less noble tasks.

The recent hue and cry over removing the Confederate battle flag from southern statehouses has raised similar concerns. In the wake of the Charleston tragedy, major online and storefront retailers have refused to sell Confederate flag merchandise (in much the same way that Ebay has a longstanding policy forbidding the sale of products promoting malevolent political ideologies such as National Socialism). (Here‘s the WSJ’s version of the announcement.) Since many games treat the Civil War, the issue has spilled into the gaming world. Apple has joined others in removing apps deemed to use the flag offensively, a move that has upset makers of Civil War-themed games. Gamers have noted that Battle Cry, a popular Civil War game, was removed from Amazon’s listings (though, if so, it was only temporary, as I found the game with no problem). There has been much online discussion about the whole issue (see some BGG conversations here, here, and here), with the typical mix of those who fear that social progressivism will limit speech (yes, games are speech), and those who argue that such fears are over-reactions.

We will see how it settles, but I sense considerable over-reaction on both sides. Amazon did not return my inquiry before this was published, but certainly it seems absurd to summarily remove from sale all Civil War-themed games. The Guns of Gettysburg was reportedly temporarily removed, despite that it doesn’t even feature a Confederate flag on the cover, only on some of its pieces. At the same time, the boardgame forums are filling with snarky, sarcastic comments about “political correctness” and government censorship (of which there is absolutely no evidence here).

We will see how it settles, but I sense considerable over-reaction on both sides. Amazon did not return my inquiry before this was published, but certainly it seems absurd to summarily remove from sale all Civil War-themed games. The Guns of Gettysburg was reportedly temporarily removed, despite that it doesn’t even feature a Confederate flag on the cover, only on some of its pieces. At the same time, the boardgame forums are filling with snarky, sarcastic comments about “political correctness” and government censorship (of which there is absolutely no evidence here).

I suspect that in a panic online retailers simply purged their lists of anything that smacked of the Civil War, and then took the time to review many items and return them to the list. Over-reaction of risk-averse retailers? Surely. Government takeover? Of course not. The heat of the moment was brief, and is passing quickly. I have had no problem finding these games online. Search “confederate flag” on Amazon and you will still find no shortage of complete absurdities, including this horrible gem, which I won’t promote with a link:

But the kinds of questions such moments raise are unlikely to go away. And I have barely scratched the surface. In reading over this very long post, I’m struck at the innumerable small points that beg to be expanded into larger considerations. For instance, my brief reference to zombies invites much larger discussions of the African roots of that trope, and its complicated significance in American popular culture. I predict that before too long, we will be thinking of games as important pieces of cultural representation, as validly and deeply considered as novels or films.

What exactly, then, is the relationship between games and malignant cultural representations? I’m still working through these issues, trying to reconcile my gamer’s heart with my role as an academic who studies race, slavery, and social justice. Not to trivialize DuBois, but it would be nice to merge these two unreconciled strivings. So please bring it on. I’m curious to hear the thoughts of others, in both communities.

[1] There are exceptions to all this. While I’ve been describing trends in “Euros,” the American boardgame market has unabashedly stuck to its conflict-oriented themes. Sometimes affectionately dubbed “Ameritrash,” these games tend to be marketed to a younger audience. They are built less on elegant and abstract mechanics than on flashy components and direct conflict, often themed around armies and fighting creatures or machines. While the distinction between Euro and Ameritrash games has diminished over time, the general distinction is still conceptually useful.

[2] Dale Yu, “Developing Dominion: What Game Development Is All About,” in Mike Selinker, The Kobold Guide to Board Game Design (Kirkland, WA: Open Design, 2011), 78.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

As an Afrrican American board gamer, I hear you. I write about games for a paper in my hometown of Houston called the Houston Inner Looper. I am super glad I have a spouse also African American, who likes board games too. On the subject you are speaking on, we own Five Tribes with the slave cards and feel it fits the theme of 1001 Arabian Nights. In the game Lords of Waterdeep, which is set in the Dungeons and Dragons world, the expansion has a slave market. We still play it. Now with Freedom, we decided we don’t want the game as it hits to close to home. In the game if the slave catcher gets to your blocks, you know what happens. That’s painful, so we won’t have the game in our collection. On BGG, I have had a few conversations about this, the confederate flag and race to a huge majority of folks that don’t look like me that can seem to grasp what my problem is. Well, one, we are seen sometimes as an Anomaly in the hobby. Let’s work on that then we can start with the next issue.

Excellent write up on games and their historical elements. I’m with you on Freedom as well. I’m white, and as much as I liked the game, it was not something I felt comfortable adding to my game library. I feel the same about the flag issue as well, that companies were CYA and would revisit items for merit. It is an inelegant solution In any case.

I wondered if you might also explore game playing in the African American community. In particular as someone who both works at and attends Boardgames conventions, there seems to be a smaller representation of African Americans at such venues compared to the general population. Since my own experiences are limited I would trust to others to correct that impression.

thanks, Miklos, for sharing your thoughts and experience. so you’re ok with the presentation of slavery in Five Tribes, but not with the possibility of leaving slaves in bondage in Freedom. that’s really fascinating. i’m sure there are many thoughts on this as there are gamers, but i’d be really interested in sounding out other games of African descent to see how these feel about this.

I think for us with 1001 Arabian Nights, if people of this heratige have a problem with the game, I totally understand. It hits close to home. I think it’s the same for us with Freedom, it hits way to close to home. I would like to hear more voices on this also from fellow gamers of African descent.

Hi there,

I run a board games group in Qatar. I have a copy of Puerto Rico but haven’t brought it: and it could be perfectly rethemed for Qatar, better than the original, without changing the colour of any of the pieces, just trying to find a third+ commodity beyond oil and gas, and upping the tech of the buldings. [I note to myself that I almost said ‘reskinned’]. Perhaps this would fly off the shelves in the run up to 2022 … It’s awkward fighting for someone else, until you realise that an injury to one is an injury to all,

I’m getting to the point where I think I can make a worthwhile game contribution – some people have a book in them, I think I have a game – and looking around, find that seemingly *none* of the games seem to be from a struggle perspective. (With the noble but rather clunky exception of Bertell Ollmann’s Class Struggle, from Avalon Hill). Even the liberal ones are written from the point of view of states or corporate bodies doing nice things *to* people or *for* people. Maybe a ‘survival horror’ game of everyday life? There is now the grim, but excellent ‘This War of Mine’ about the Bosnian conflict, on PC. Maybe what is needed is a ‘This war of mine’ brought to the office, the shop, the high street? Like Arkham Horror but all the Deep Ones are middle management? Or a ‘They Live’ theme?

I guess I’m rambling, but I would be interested if anyone knows of any games in this vein, and if they’re any good.

Regards,

Simon W.

Thank you for the thought-provoking article. I’m curious if you’ve read Bruno Faidutti’s article on the representation of colonialism and fetishization of Eastern culture in board games? It’s a subject that I’ve been really interested in and it’s great to hear and read more on it. For context, I’m 3rd generation Malaysian Chinese, residing in Australia. Although our cultural experiences are very different, European colonialism has been a constant spectre, and I’ve been trying to learn more of how it’s been represented in my chosen hobby as well.