Jean-Michel Basquiat: Black. Intellectual. Historian.

[CLICK IMAGES FOR HIGHER RESOLUTION]

Last week I moved to Harlem. On Sunday I spent the day with Jean Michel Basquiat. It was a closure of sorts but an opening of others. As the last day of an exhibit that began in April, I was unsurprised to shuffle through an eerily empty queue to voluntarily pay my mandatory donation to the Brooklyn Museum of Art. I got there early. A certain number of hours later, I was unsurprised again. This time, to find a line of hundreds stretching out the door hoping to catch one final glimpse of what I just saw. While Brooklyn was sleeping, I was being awakened.

It is exceedingly rare to find an artist with the staying power, reach, and international appeal that Basquiat has maintained in the 27 years since his death. Next year the world will be consciously without him for more years than it was with him. Yet, somehow, he manages to remain as alive, thoughtful, and relevant as ever. Rather than historicize Basquiat’s emergence from the postmodern, deindustrialized ruins of New York City in the 1980’s, I’d rather examine him as a historian (and an intellectual one at that). Indeed, this exhibit, if nothing else, demands that we see Basquiat not as a mere subject of history but as an author attempting to shape and contend with a very particular historical narrative that far pre-dated him.

ORIGINS

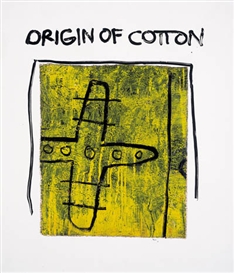

Graffiti reclaims urban space. It makes the public private and the private public. The built environments of the state and private industry are forced back into public use. The inner-artistic expressions of self-conscious subjects are simultaneously offered up for all the world to see. Yet Basquiat’s work did more. Not only did he reclaim and remake urban landscapes, he also uncovered their histories and their very constructedness. In short, he exposes the underlying reality of histories unseen. Take this clip from the installation:

Here Basquiat forces observers to contemplate the origins of industrialization, cotton, slavery, race and capitalism all within the blighted context of a postindustrial North. By forcing the geography of cotton to New York City, Basquait anticipates the work of historians such as Sven Beckert, Seth Rockman, and Edward Baptist who are in the process of decoupling slavery from its shackles in the South and exposing it as the truly national (and international) project that it was. Basquiat forces New Yorkers to realize that their boroughs, like all American cities, are built on slave capital. Yet the “of” in the “ORIGIN OF COTTON” can also be read another way. Cotton had an origin, but it also WAS an origin. Not only does this insistence demand an acknowledgment of a traceable, living, breathing past—hardwired into the landscape of cities— but it also understands that the kingdom of cotton of the past is a necessary origin for the present (post)modern world at large. Not coincidental to the claim that Basquiat is a historian of ideas, the entire pursuit of origins is a thoroughly historical endeavor. From Origins of the New South to the origins of American identity, to the countless subtitled books claiming to uncover the origins of this or that phenomenon, Basquiat, like all historians, seems endlessly enamored with uncovering origins (teleological risks be damned). Whether or not Basquiat was aware of the thesis already bubbling among historians in the 1980’s, that modern factories and assembly lines were inspired by sugar plantations before being perfected in cotton fields is unclear and, ultimately, unimportant.

Artists know things intuitively that it often takes historians years to discover. Basquiat’s insistence that cotton, and all that it represents, must be understood as both an origin and as having an origin continued through at least five other works (not part of the exhibit) where Basquiat repeated this phrase—at times with his trademark copyright.

The copyright itself also bears further reflection. In one sense, Basquiat was obsessively aware of the marketplace and the copyright was a way to let the art world know that he was the owner of his own phrases, ideas, and personhood. At the same time, his deployment of the copyright attempts to make a mockery of the very idea of owning ideas. It also pushes back against the modern world’s attempt to commodify everything through a legally enforced intellectual property regime (a key foundation for the development of global capitalism). His use of both the copyright and the trademark throughout his work are at once an insistence on recognizing the black right to property and a simultaneous rejection of corporate capitalism. This second aspect is on full display as he purports to copyright “URINE” “BABOON”, and the expression “HEY” in this piece conveying the unfettered expansionist marketplace and its intent on monetizing everything in a totalizing way:

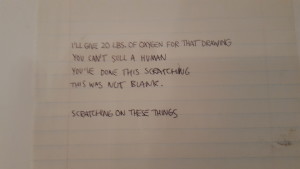

Elsewhere Basquiat also plays with this theme of ownership within the context of slave racial capitalism. He insists that “YOU CAN’T SELL A HUMAN” even within

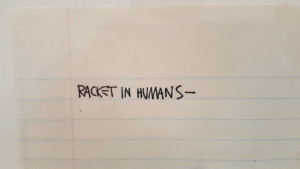

the globally widespread and historically long lasting “RACKET IN HUMANS.”

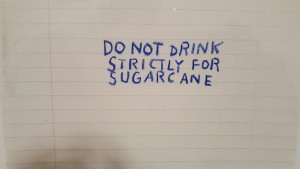

The plantation (both modern and historical) looms large in Basquiat’s work as one can easily imagine a slave on a plantation being told “DO NOT DRINK” the water because that water is “STRICTLY FOR SUGARCANE.”

TEXT

The focus of the installment was clearly text. History masquerading as poetry and vice versa. In these crafted, intimate notebooks—deconstructed and reassembled in sterile, curated glass—museum go-ers were asked to enter the mind of a black man who lived his life between his ears at least as vibrantly as he did on his canvas. What emerges is vision of the past rooted in exclusion, negation, and overwhelming weight. A prodigious outpouring of this (con)texual past was, for Basquiat, what transformed his work into a chaotic glimpse of tentative liberation.

Cultural appropriation and the great transatlantic tradition of white artists plundering black folk culture is a recurring theme. Take Basquiat’s rendition of Jewish blackface performer Al Jolson:

While Jolson specifically, and blackface in general, is currently undergoing an incredibly nuanced reassessment by historians, one wonders if Basquiat may have been wrestling with many of the same complexities of subjectivity in this rendition of Jolson—whose eyes look deathly freighted behind the mask of blackness. Yet the title insists that this WAS Jolson—his essence—terrified in his desire to imitate and confront modernity through its prototypical navigator: the black subject. As other scholars have noted, the degrading troupes in minstrelsy were often wrestled with by marginalized performers—both black and Jewish—who often worked to point out the very maskedness of the performance itself while mocking white audiences for believing the act to be anything but an act. In this way Basquiat’s life and interaction with the racism of the art marketplace may have been very similar Jolson’s and perhaps more directly (and in more was that one) to Bahamian born black minstrel performer Bert Williams’s. The overall American infatuation with minstrelsy also constituted part of a lasting American tradition of putting black people and black culture at the center of American popular entertainment even as black bodies themselves were brutalized and desecrated. As Jolson and Williams became ‘black’ in their performances they were certainly acting within a field that reinforced racist imagery but at the same time both men were trying to undo that imagery from within through subtle performances and civil rights activism off stage.

In many ways these tensions continued through jazz, the blues, rock and roll, and now hip hop. This piece bemoans the erasure of blackness (rather than its embrace) that has become the norm in American pop culture:

This reference may have been to the obscure 1969 Led Zeppelin song “The Girl I Love She Got Long Black Wavy Hair” which was a pseudo-cover of an even more obscure Sleepy John Estes blues ballad “The I Girl I Love She Got Long Curly Hair.” Even if Basquiat’s notoriously photographic memory of popular culture did not stretch back this far, the point of the piece— and the “CONSIDERABLE CLOUDINESS” on the topic of black culture in American life—remains. It works as history as well. Black artists in the past write a song. White artists in the present do an awkward rendition. Americans in the future discard the nappy roots of the song and the black artists who sang it. For those interested in Basquait’s prophetic accuracy, at least a few white girls did in fact sing the song (and quite horribly) a little over 20 years later.

Speaking of prophesy, several of Basquiat’s notebook pages can be read directly against the contemporary landscape of 2015. The artist appears through his notebooks to return from the grave to comment on black life today. For example, one might think about “THE AREA CODE OF ST. LOUIS” before and “PRIOR TO THE ASSASINATION” of Mike Brown:

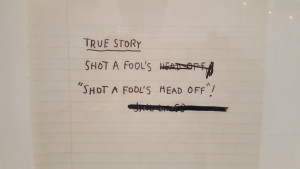

The harrowing “TRUE STORY” that a perpetrator “’SHOT A FOOL’S HEAD OFF” takes on an entirely new meaning when you realize that this expression was not uttered in the context of the crossed out “JAIL LINGO” (yet) but instead resemble the likely words of the police officer that shot Sam DuBose.

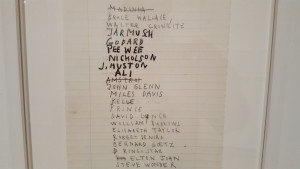

George Zimmerman’s vigilante justice is harkened to through the “BERNARD GOETZ” case which is found buried and juxtaposed against a list of actors, artist, directors, and celebrities that Basquiat either admired or (in the case of Madonna and Neil Armstrong) used to admire:

In yet another reference to the criminalization of black bodies, Basquiat mocks a presumably white woman worried about black male violence by telling her “DON’T SCREAM I WANT YOUR PURSE”:

The fact that black America has been the “HOME WORKBENCH” for these kind of mass “SURVELENCE UNDERTONES” even when we now have “VERN AS THE PRESIDENT” is not lost on the artist either:

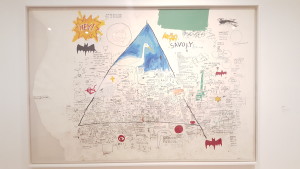

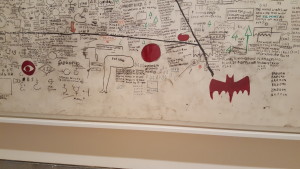

Yet these odes to the present should in no way obscure the fact that Basquiat was urgently concerned with the past. Being in league with both revisionist and post-revisionist historians, Basquiat explicitly spoke on behalf of the “VICTIMS OF EMBELLISHED HISTORY.”

His “HISTORY OF THE WORLD” is laced with “BOOTY,” “LOOT,” and “RANSOM.”

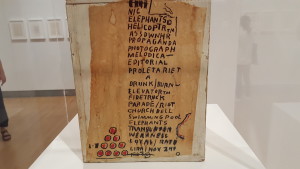

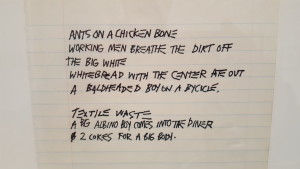

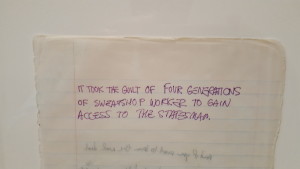

Marx is everywhere with references to an intentionally misspelled “PROLETARIET” signaling a skepticism towards high brow Marxism in favor of a more organic anti-capitalism lead by unschooled workers. This is part of Basquiat’s move into labor history where “WORKING MEN BREATHE THE DIRT OFF” after being regarded as little more than “TEXTILE WASTE.” “THE GUILT OF FOUR GENERATIONS OF SWEATSHOP WORKER[S]” screams aloud in these works:

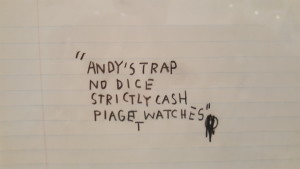

Basquiat also seems keenly aware and self-reflexive of these connections to the scholarly world. A “WATCH[ING]” Swiss theorist Jean Piaget can be found along with a negated copyright symbol as Basquiat attempts to navigate his friend Andy Warhol’s “TRAP” of “STRICTLY CASH.”

Basquiat’s cynicism towards professional scholarship and his own station within in, can be found through his odes to classic Greek and Roman philosophers as well as this overt critique of the formal educational establishment:

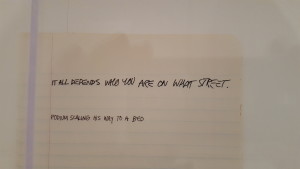

Basquiat further lampoons so-called scholars who he sees as merely pontificated on a “PODIUM SCALING HIS WAY TO A BED”

His summation of the academic “ideology of complexity” (so astutely noted by Kwame Zulu Shabazz during a recent Twitter discussion of Pan-African communism here on AAIHS), is summed up by Basquiat’s poststructuralist truism of epistemological relativity: “IT ALL DEPENDS WHO YOUR ARE ON WHAT STREET.” This ability to sum up and belittle formal academic discourse ironically places Basquiat firmly within it. His critiques should resonate with scholars (or at least it does with this one) even as they unsettle many of the assumptions circulating within the ivory tower.

CHILDLIKE?

As powerful as Basquiat’s work is, it was not at all helped by the arraignment of the exhibit itself. Indeed, Basquiat’s notebooks mange to succeed in spite of its curators rather than because of them. The wanton failure begins at the entrance were observers are prepped to see…get this…“deceptively childlike imagery.”

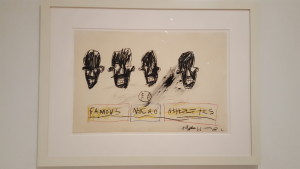

Being generous, perhaps this horribly composed phrase meant to say “you think these images are childlike but, don’t be deceived, they are really quite complicated.” However this phrase more closely resembles a grave insult. It patronizingly concedes Basquiat’s “sophisticated poetic voice” but implies that he was only capable of primitive “childlike imagery.” Basquiat himself often had to counter such racist claims during his lifetime by insisting to one white interviewer “[b]elive it or not, I can actually draw.” As Basquait famously said in this same interview with Marc Miller, he draws people crudely because “most people are generally crude”. If anything, the world itself was a crude childlike place in Basquiat’s eyes. He just accurately drew the crudeness and chaos exactly as he saw it. He drew reality. He was seeing beneath the surface of people—underneath their fluffy facades—to expose their cruelties, their ugliness, and their systemic inhumanity. This brutal confrontation between the projected public self and the miserable hidden self is part of what philosopher Jacques Lacan has so graphically called “symbolic castration.” This fear of such an exposing rupture is why debutantes are often jarred and repulsed by looking at a typical Basquiat painting like this one:

Yet when one looks closer, one finds a historical chronicle detailing the long history that went into producing such demonic transformations in human subjectivity. References to the “WEST INDIES,” “CRISPUS ATTUCKS,” and the “SEVEN YEARS WAR” all collide and compete for space:

In this way Basquiat paints the way that Ta-Nahisi Coates writes. Theirs is a brutal realism that refuses to let human beings bask in a self-fashioned glory of their own design. Basquiat also thinks in a way that is familiar to Coates, meditating in the line below about “THE DREAM.”

This play on the word“accept” as an injunction versus the syntactically implied “except” as an exception is exactly what I was aiming towards in my review of “Between Me and the World.” In one sense “THE DREAM WILL NEVER DIE” and we must “ACCEPT THE REALITY OF LIVING IN THE STATES” in a Coatesian kind of way (yeah I did it, copyright SAMO). But in another sense, “THE DREAM WILL NEVER DIE [EX]CEPT” when one is aware of the “THE REALITY OF LIVING IN THE STATES.” It is exactly this “REALITY” that exposes “THE DREAM” and makes it vulnerable to death. The brutal realities that Basquiat and Coates convey help broadcast the hallow promises and empty gestures that an American Dream rooted in slavery, capitalism, individualism, materialism, shallow amusements, and a horribly warped sense of meritocracy entail.

The curators, however, left no stone unturned in their efforts to undue Basquiat’s critique on this point. They went to seemingly great lengths to create a promiscuous environment for the shameless commodification of his art. At the end of the exhibit patrons were asked to marvel at one final Basquiat masterpiece while being commanded with no sense of irony to “SHOP.”

Inside the horrifically furnished yellow gift shop where coffee mugs, tote bags, and baseball hats that could be bought on the cheap as part of a blowout 40% off clearance sale. While Basquiat certainly struggled during his lifetime with his place in the art world’s market economy, he surly would be rolling over in his grave at the sight of this defiled abomination.

Yet perhaps we should expect nothing less from the same museum that is also currently bringing us an installation bent on worshiping “Sneaker Culture.” Despite the weak attempt to grapple with the gendering of the sneaker, this installation serves as little more than a virtual advertisement for Nike and other manufacturing conglomerates. Consumers scan the glass cases to sort out their preferences while salivating and fantasizing about their next purchases. Just down the hall, Basquiat’s ghost once again cries out in anguish.

LEGACY

Like all great artists Basquiat imposed his own lens on the world and its history. He forced viewers to see that world anew through his eyes and his mind. His work has clearly inspired the activist/artists of Adbusters and other culture jammers who attempt to short circuit the otherwise hegemonic programming of neoliberal values and consumer capitalism disseminated through corporate media. Edward Herman and Noam Chompsky’s Manufacturing Consent might have fallen right out of a Basquiat painting and on to an Andy Warhol canvas in the pop art tradition. Director John Carpenter’s They Live seems likewise influenced by Basquiat whose work above all else tried to uncover the hidden transcript behind the official discourse. For what it’s worth, Jay Z, Rick Ross, and the entire hip hop world of course loves to namedrop Basquiat at any given opportunity even as they widely disregard the bulk of his messages.

For historians and scholars however, Basquiat presents a different challenge. His work destabilizes any neat lines we are apt to draw around art, scholarship, the intellect, the aesthetic, and high culture. He explodes the binaries between text and image, emotion and intellect, artist and scholar, history and future. He shows that our general belief that historians only exist in classrooms, libraries, and book talks is erroneous. Artists, workers, and everyday people are historians too. Lest we forget that Howard Zinn credited the bulk of his historical knowledge not to his formal training at Columbia University but to the music of Woody Guthrie and the political narratives of labor activists. T. Thomas Fortune, George Washington Williams, and a host of other black historians that followed them often produced groundbreaking historical works rooted in a black experience while doing a day job that was far removed from that of a professional historian in any traditional sense. Basquiat reminds us that bottom-up history comes from all directions. Indeed the term itself is desperately in need of revision. Thomas Holt, Catherine Brekus, and other historians have already begun doing just that, recently thinking instead about a new approach to ‘the history of ordinary people.’ Yet Basquiat himself defies even this framework as he was far from ordinary. Jordana Moore Saggese’s recent work captures this perfectly in perhaps the definitive study thus far on the man and his art. Historians must certainly continue this important work on Basquiat. But let us not forget Basquiat’s important work on us.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I enjoyed this… Thank you for sharing…