From ADEFRA to Black Lives Matter: Black Women’s Activism in Germany

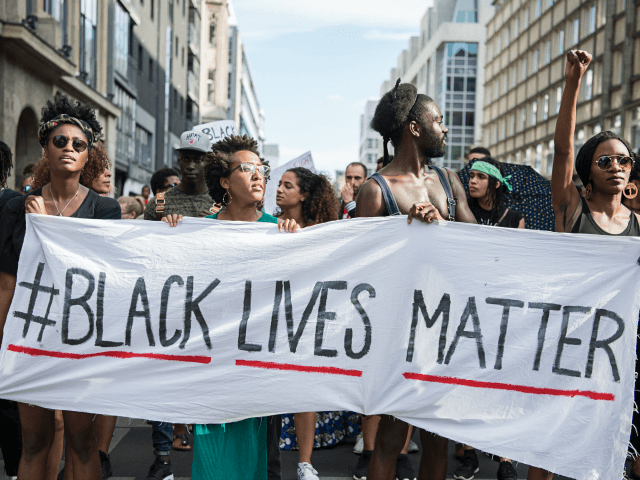

On Saturday, June 24, 2017 at 4:30pm, a Black Lives Matter (BLM) protest took place in Berlin, Germany with thousands of people expressing solidarity and promoting awareness of racial injustice. The event built from the momentum of two BLM marches that occurred last summer. Initially meeting at the 2016 BLM marches, Mic Oala, Shaheen Wacker, Nela Biedermann, Josephine Apraku, Jacqueline Mayen, and Kristin Lein remained in contact and eventually established a Berlin-based multicultural German feminist collective. With their new group and local connections, they planned the 2017 demonstration as a part of a month-long series of events, which included film screenings, poetry readings, workshops, exhibitions, and more.

Taken together, these events highlight the diversity of Black protest and activism within the German context. Using these events, especially the protest, the organizers publicly drew attention to instances of racism and oppression and attempted to gain visibility for Black people in Germany and beyond. The different events as well as the BLM Movement in Berlin represent the conscious efforts of these feminist and anti-racist activists to not only engage in practices of resistance, but to create and own spaces of resistance, solidarity, and recognition within a majority white society. In this way, they demand their “right to the city” and continue to make Germany a critical site for blackness and the African diaspora.1

Embracing black as a collective identity and advancing intersectional politics, these women envision the German BLM Movement to be a space for individuals to develop new critical methods that will help them acknowledge their overlapping oppressions in order to create an alternative society. They are not unlike their BLM counterparts in Britain, France, or the United States, in that they encourage social action by campaigning against state violence and for racial and gender equality and basic human rights.

Moreover, BLM activists in Berlin want to transform German society by underscoring the persistence of racism in a country that has dealt, and continues to deal, with its fair share of racial violence, including the Herero and Nama genocide in Namibia (1904-1908), the Holocaust, the 2005 murder of Sierra Leonean Oury Jalloh while in police custody and the Neo-Nazi killing spree (2000-2007). Hyphenated Germans still struggle with the public perception that they do not belong within the national polity. One of the German BLM’s intentions, therefore, is to dispel the myth that Germany is no longer a racist country and to show how much work the country needs to do to dismantle institutional and everyday forms of racism.

BLM organizers such as Wacker, Biedermann, Apraku, and Mayen are also building upon a tradition of Black women’s radical activism in Germany. For example, Fasia Jensen was a Black German political songwriter and peace activist who remained active in left-wing internationalist and anti-racist circles in the post-1945 period. Highly visible and prominent, she produced songs that addressed equality. Black German women such as Ika Hügel-Marshall were active in the West German feminist movement in the 1970s. In the 1980s, Black German women, including Katharina Oguntoye, May Ayim, Eleonore Wiedenroth-Coulibaly, Helga Emde, and others, united to establish the modern Black German movement, and they were motivated in part by Caribbean-American feminist poet Audre Lorde.

Lorde was a visiting professor teaching courses at the Free University of Berlin (FUB) in 1984, which a few of these women attended. Black German women also cultivated connections to her outside of the classroom. Lorde emboldened Black German women to write their stories and produce and disseminate knowledge about their experiences as women of the African diaspora in Germany. Inspired, Oguntoye, Ayim, and Dagmar Schultz, a white German feminist, produced the volume Farbe bekennen: Afro-deutsche Frauen auf den Spuren ihrer Geschichte in 1986 (later published in 1992 as Showing our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out). The volume helped Black German women and men connect and socialize with one another and forge a dynamic diasporic community after years of isolation in predominantly white settings.

Farbe bekennen also signaled a new stage of Black German activism. Ayim, Oguntoye, and other Black German women and men co-founded the Berlin chapter of the Initiative of Black Germans (Initiative Schwarze Deutsche, ISD). Additional ISD chapters emerged in various cities, including Frankfurt, Dusseldorf/Cologne, and Munich. Once the Berlin Wall fell, chapters sprung up in cities in the former East. In addition to ISD, Black German feminists and lesbians also created the feminist organization Afro-German women (Afrodeutsche Frauen, ADEFRA), which served as a sister organization to ISD. Black German women formed regional ADEFRA chapters in major cities across Germany.

Both organizations were political as well as cultural. Their members collectively organized to fight against racism, raise their voices, demand dignity, change racist stereotypes of black people, obtain recognition about their social realities, and change the presumption that being Black and German was a contradiction. These groups were welcoming of individuals from other parts of the African diaspora as well as Asian Germans. ISD and ADEFRA members hosted events collectively and separately that catered to Black people, but they also opened their events to white Germans and other minorities. More importantly, Black Germans used their organizations to produce Black spaces that enabled them to achieve visibility and to invent new traditions that helped Black Germanness be articulated in Germany.

Black German feminists and lesbians recognized the necessity of establishing their own empowering and inclusive spaces in a majority white West German society that simultaneously othered and ignored them. This was especially important since several of the ADEFRA activists’ involvement in the mainstream German feminist and lesbian movements often entailed marginalization and erasure as Black women. Some of the founders of ADEFRA were Katja Kinder, Katharina Oguntoye, Ja-El, Eva von Pirch, Judy Gummich, and Jasmin Eding. In addition, Ayim, Ria Cheatom, Marion Kraft, and others also helped with early efforts. Some of these women were lesbians and already were participating in their local ISD chapters as well as other feminist and anti-racist initiatives. Ultimately, the establishment of these grassroots groups continued to broaden Afro-German women’s sense of community and spread ideas about Black feminist and diasporic practices.

Some of the organizers of the BLM Movement represent a direct line from the Black German movement of the 1980s and 1990s. In some cases, this activism even dates back to the colonial period. As the recent BLM events in Berlin demonstrate, Black German women’s radical activism continues to have a place in Germany. The BLM’s month-long series of events, like earlier Black German events, emphasized the pivotal role that race still played in society and helped to produce knowledge about the plight of Black people in Germany and elsewhere.

These events in Germany also served as opportunities for intellectualism and empowerment. They also garnered support from the local ISD group as well as activists from ADEFRA (now Generation ADEFRA). Producing spaces that rendered blackness visible, these women’s activism reflect their efforts to not only forge solidarity with others, but be agents of change and to underscore that Black lives matter in German society.

- Henri Lefebvre, “The Right to the City,” in Writings on Cities, eds. and trans. Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas (Cambridge: Wiley-Blackwell, 1996), 147-159. ↩