Demystifying the 13th Amendment and Its Impact on Mass Incarceration

We’re learning a lot these days about the historical roots of mass incarceration. Michelle Alexander’s wildly successful book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness now has a cinematic companion, Ava DuVernay’s documentary “13TH.” The film’s powerful overview of the crisis of mass incarceration from the Civil War to the present has earned it plaudits from critics, activists, and scholars. But we need to revisit its faulty foundational history.

DuVernay’s title refers to the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery throughout the country when it was ratified in 1865. In the documentary, Jelani Cobb argues that the amendment created a “loophole” that permitted the massive criminalization of blackness that has defined the post-emancipation experience from Jim Crow to the prison industrial complex.

The critical text reads:

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

The film argues that the central dependent clause of this article is the problem. The country prohibited people from being deprived of their liberty, but with a critical exception: they could now be imprisoned, whether on chain gangs or in modern penitentiaries. As the film’s intertitles state, the African American went “from slave to criminal with one amendment.”

Many have adopted and extended this argument. One author commenting on the documentary calls the exception clause “a poison pill, a trapdoor, an escape clause” that permitted the persistence of slavery. He quotes another: “The 13th Amendment says slavery is still legal. Slavery is legal in prisons. You better wake up and see this conspiracy for what it really is.” Another claims, “in 2015, the 2 million (largely Black) people incarcerated in America are legally considered slaves under the Constitution.”

All of these have consequences. There is a Change.org petition to “close the 13th Amendment Slavery loophole.” In states whose constitutions echo the language of the amendment, like Wisconsin, efforts are afoot to strike the language. In Colorado, a ballot initiative to do this recently failed.

In a nutshell, the argument is this: The country did the right thing in passing an amendment intended to make all people equal, but some connived against that noble aim in permitting, and then exploiting, the mass incarceration loophole. When we put these claims to the test with a closer look at the Amendment and its origins, we learn that they bear little resemblance to the actual history.

First, the “loophole” argument imputes to its framers and judicial interpreters a conspiracy against intentions of full equality that the amendment never included in the first place. All the Thirteenth Amendment did was abolish slavery; it stood virtually moot on the meaning of freedom. This was by design. Antislavery legislators wanted a more comprehensive measure, but only by compromising on its vision would more conservative legislators let it pass. It took later amendments and laws to define freedom: the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (civil rights), the Fourteenth Amendment of 1868 (citizenship), the Fifteenth Amendment of 1870 (voting rights), and others.

Second, on its face, the language of the Thirteenth Amendment’s “exception clause” offers no mechanism to actively promote incarceration. Instead, its obvious purpose is to ensure that none mistake the prohibition on racial slavery for a prohibition on criminal incarceration. Given the novelty of emancipation at the phrase’s origin, that was not pointless: surely the abolition of slavery should not mean that no one (black or white) could ever be incarcerated for crimes they committed, right?

The exception clause alone did nothing to promote racial oppression. Search in vain for legal cases in which the clause was used to argue for the legality of any form of punishment. Instead, we see the opposite, as in in U.S. v. Ah Sou, C.C.A.9 (1905), wherein the court used the clause to argue against deporting a Chinese woman because it would have returned her to a state slavery in China. To justify their oppression, white supremacists used much more powerful and overt legal devices than slippery language in the Thirteenth Amendment. Jim Crow and mass incarceration would’ve happened with or without the exception clause.

The clause itself elicited little discussion in 1865, largely because it was not new at all. We easily forget that by end of the Civil War the United States had already experienced the abolition of slavery in northern states. Vermont had written slavery out of its state constitution in 1777; Massachusetts abolished it through judicial rulings in the 1780s. States such as Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey passed gradual emancipation laws that phased it out over time.

When the country expanded into the Northwest Territory in 1787, the very year delegates met to devise a new constitution, Congress decided that slavery would be prohibited in the new lands. Compare the slavery prohibition of the language of the Northwest Ordinance with that of the Thirteenth Amendment:

1787: “There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

1865: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Everyone in 1865 openly acknowledged and discussed this debt to the Ordinance of 1787. They were not the first. The language of the Ordinance echoed in the constitutions of every state carved out of it (see Minnesota’s here), as well as many far western states. The exception clause had long served the purpose it served in 1865 and 1787—to distinguish, not merge, slavery and criminal incarceration.

By 1865, the exception clause had become boilerplate. It drew attention only from Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, who objected to it precisely because it created confusion. While in 1787 there may have been need to distinguish between slavery and penal servitude, Sumner argued, “that reason no longer exists.” The clause should be excised, he urged, because it had become pointless: “’imprisonment’ cannot be confounded with this ‘peculiar’ wrong,” he stated, referring to the “peculiar” (i.e., specifically southern) institution of slavery. Following Sumner’s advice and leaving the exception clause out of the Thirteenth Amendment would have certainly obviated our present confusion over its meaning. But since different means were used to implement Jim Crow and mass incarceration, they would’ve happened anyway.

The Thirteenth Amendment did nothing to promote mass incarceration in freedom, but neither did it do anything to limit abuses of the criminal justice system that stopped short of actual slavery. The law had long distinguished between slavery and incarceration, and no one intended the Thirteenth to erase that distinction. Its only intent had been to prohibit the holding of people as property. When civil rights advocates in the 1870s began arguing that discriminatory laws conferred a “badge of servitude” on blacks, they were roundly rebuffed because the measures were race-neutral on their face.

Upon emancipation, the freedpeople quickly learned that this was a distinction without a difference. This is what people mean when they claim that emancipation “didn’t matter.”

But it did. Mass incarceration was the product not of slavery but of freedom—of a liberal order premised on individual rights of property, particularly in self-ownership. Liberal legal regimes had destroyed slavery by defining it as a barbaric rejection of the modern, only to then promote forms of mass incarceration as legitimate if unfortunate necessities of life in “freedom.”

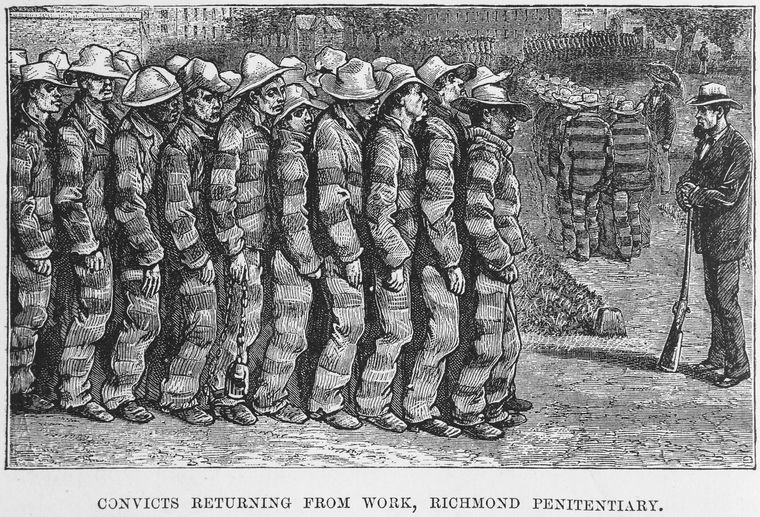

“13TH” makes the laudable case that racially-specific, for-profit exploitation of a criminalized underclass should be no more legitimate than was slavery. But in mischaracterizing the role of the Thirteenth Amendment it underplays the depth of the problem in both history and the present. There was no need for secret language or tricky loopholes. Southern state governments worked openly to pass the legal mechanisms that criminalized blackness and poverty, from black codes and apprenticeships laws to vagrancy provisions and convict lease systems. The culprit was not the persistence of an old and rejected labor regime, but the emergence of new ones, which the state found much easier to justify.

Slavery and mass incarceration are not the same. All forms of racial oppression are not forms of slavery; rather, slavery is one form of racial oppression. Mass incarceration is another. While it may help to end it by associating it with an institution we abolished, it is not the remnant of a barbaric and outmoded system but the product of modern society. The problem isn’t the persistence of slavery; the problem is how a system that has always promised justice for all always seems to find ways to deny it to some.

If we can only see ongoing racial oppression as a remnant of slavery, then we can’t see it as a problem of our own age. And if we can’t understand mass incarceration as a problem of our own age, we can’t critique the mechanisms that foster racial and economic inequality in a system that is supposed to be blind to both.

But just as it became possible to topple a world in which slavery was an unquestionable norm, so too it can become possible to topple a world in which mass incarceration and other systematic forms of inequality are an unquestioned norm. We need only think such a world into existence.

Patrick Rael is Professor of History at Bowdoin College. He is the author of numerous essays and books, including Black Identity and Black Protest in the Antebellum North (North Carolina, 2002), and his most recent book, Eighty-Eight Years: The Long Death of Slavery in the United States, 1777-1865 (University of Georgia Press, 2015).

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

It should be remembered that until recent times whites were the main occupants of prisons. Incarceration was not the tool of enslavement for African-Americans. Rather, it was sharecropping, peonage, the general system of Jim Crow, and fascist terror. I think this emphasis on the 13th Amendment definitely muddies the water, sounds militant but in reality distracts from the real enslavement of Black people post-Civil War and up to the present.

“It should be remembered that until recent times whites were the main occupants of prisons.” I don’t know what ‘recent times’ you are meaning, if you mean prior to the 13th Amendment, I would think it was because during those ‘times’ blacks had a greater chance of being killed than be duly convicted.

I also don’t understand how any emphasis on the Amendment can sound militant?

I too was penning a critical response to this blog post but now will (gratefully) let the above suffice, although my argument was largely limited to “[t]he fact is that there are innumerable cases in which state and federal courts have used the exception clause to quash prisoners’ attempts to call upon the 13th amendment as means of escaping slavery and/or involuntary servitude.” As Colin Dayan likewise makes painfully plain in his little book, The Story of Cruel & Unusual (Boston Review/MIT Press, 2007), “after emancipation, to the extent that former slaves were allowed personalities before the law, they were regarded chiefly –almost solely—as potential criminals. [….] So those who were once slaves were now accused of petty crimes, convicted and jailed, and forced to labor in the convict-lease system in which private companies leased prisoners from the state. [….] The ghost of slavery still haunts our legal language and holds the prison system in thrall.” In other words, and as a consequence, the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishment” in the political and legal context of the conditions of incarceration and the general treatment of prisoners (including whatever human and civil rights they were thought to have or not have) was thereby narrowly and implausibly interpreted so as to essentially eviscerate the heart and soul of that Amendment. In the words of Professor Jeremy Waldron, “our jurists became adept at finding ways of saying that ‘necessary’ cruelty wasn’t cruelty.” In short, the notion of human dignity became essentially meaningless for those incarcerated, but particularly so for those of color (as we say). Many thanks to Professors Childs and Cameron.

This article is hypocritical at best. The 13th amendment was the father of the discriminatory laws that followed it such as Jim Crow . As a professor I expected you to make the connection because it these laws of injustice are strongly related.

Erratum: “As Colin Dayan likewise makes painfully plain in _her_ little book….”