A Telenovela, Slavery, and the Diaspora

A Escrava Isaura, the 1875 novel by Bernardo Guimaraes, was one of a number of late 19th century works of fiction in Brazil that focused on abolitionism. The story revolves around a young enslaved girl named Isaura, her efforts to gain freedom and become married to Alvaro, a wealthy white man who believes fervently in abolition, as well as her trials and tribulations with the plantation overseer who aims to seduce her and make her his concubine. It was quite transparently an anti-slavery propaganda novel. But it was also quite transparently an idealized romance, an effort to portray liberal whiteness as a heroic and saving grace for enslaved peoples. The novel was a huge success in Brazil and catapulted the author to immediate national fame.

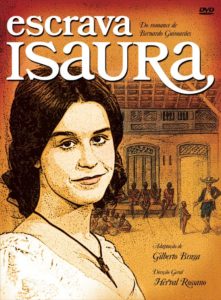

Later in 1976 the novel would be reconceptualized as a television show, or telenovela. It was wildly successful and became one of the most watched television programs in the world, broadcasted in over 80 countries. It was undoubtedly a smash success in South America but also in the Soviet Union, China, Poland, and Hungary. In fact, it was in Hungary where the most intriguing- or depending on your perspective, most comical- story about the telenovela comes to us. According to legend, it was in Hungary in the 1980s where the faithful viewers of Escrava Isaura took up collections after the final episode of the series to help purchase Isaura’s freedom.

It is a story that has never been proven and more than likely never can be proven. The mere existence and circulation of the story, however, points to a number of themes that are worth thinking about in relation to diaspora, slavery, gender, and color.

Let us start with the question of “why.” Why would viewers living in Hungary feel compelled to take up a collection to free slaves they were watching on TV? There are of course a number of possible and plausible answers to such a question, but perhaps the easiest answer can be found by first considering the profile of Isaura in both the novel and in the show. Guimaraes chose to depict her as a fair skinned daughter of a Portuguese man and an enslaved woman. In the television show, fair skin became interpreted as white skin and the actress who played the role, Lucélia Santos, was a white woman.

Although the remainder of the cast was largely black, this was a point of sharp criticism that was raised by the Movimento Negro (Black Movement) in Brazil. Nevertheless, Santos remained in the role, and thus the image of slavery in Brazil and the Americas that circulated globally through this show was one that portrayed a system that was so corrupt and so morally bankrupt that it could not be satisfied making perpetual prisoners of black people. The danger of slavery, in other words, was portrayed as beyond blackness, as something that could spread and ensnare whiteness in bondage. Sympathy for the enslaved was transformed to empathy by being indexed to familiarity, and whiteness was the form of this familiarity. This is also perhaps understandable from the standpoint of global politics if we consider that during the 1970s and 1980s there were sufficient numbers of people in Hungary who saw great parallels between their own experiences under communism and the sanitized images of slavery portrayed in the telenovela. Thus it may not have only been whiteness, and feminine whiteness, but repression which viewers in Hungary also saw as parallel enough to their own temporal existence to spur some folks towards taking up collections to free Isaura.

The phenomenon in question also raises some questions about the timeline of slavery and the understanding of that timeline outside of the West. Did some viewers of the show, many of whom likely had never gone to the Americas or even to Western Europe by the 1970s, actually believe that Atlantic slavery had yet to end? Given that the show ran from October 1976 until February 1977, and was then broadcasted globally in the 1980s, it is unlikely that they thought it was a documentary. But, by watching the show did viewers start to think the end of American slavery was just one more “lie” that they had learned about or had not been taught about adequately under communism? Or were they more attuned to, and affected by a contemporary traffic of human beings and could thus see and connect different slave trades across multiple timelines in ways that we still have much difficulty with in western historiography?

Whatever the case may be, the impact that this one fictionalized story about nineteenth century slavery in Brazil has had throughout Eastern Europe is fascinating and worthy of study. At the very least, it asks us to not only think about how audience reception can transcend a performance, but also about how the conceptual narratives and frameworks we provide for writing about slavery in the Americas are always overflowing and overlapping with different times of slavery, different moments of unfreedom, and different geopolitical constellations.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

It’s possible that people in Eastern Europe were unknowing about the end of slavery in the West.

As a personal example. I used to work in SE China in the middle 1980s. For the most part the people that we interfaced with were familiar with English. At a social gathering, the Chinese people always curious about the U.S., I remarked that the U.S. had put a man on the moon about 20 years earlier. That was news to them.

Why all this denial about the reality of white slavery? Abolitionists were right to emphasize that the corporate nature of slavery meant that it could never be satisfied with only black African “products.” Like any capitalist enterprise, it sought to expand its inventory and customer base. There is also nothing racist about emphasizing the evil of enslaving one’s own kin. The abolitionists were rightfully pointing out that the slave system violated the most sacred principles of family and tribal loyalty.

White Slaves

WHITE SLAVES – Chapter Three of “The Forgotten Cause of the Civil War:

A New Look at the Slavery Issue”

http://multiracial.com/site/index.php/2001/10/01/white-slaves/

I am not sure why the soap opera was popular outside of Brazil, but I have one idea or two about how Brazilian audiences reacted to the novela. Together with a couple of soap operas that ran during those years (Gabriela, Saramandaia, etc) Escrava Isaura was one of the main staples of the powerful media conglomerate Rede Globo. Heavily subsidized by the then military regime, the network promoted (in all those shows) a sugarcoated version of race relations in Brazil that included dense notions of racial democracy. The only depiction of slavery in television in that decade was indeed Escrava Isaura; the choice of making her completely white is very peculiar, as it helped to deracialize slavery in a country where the vast majority of slaves were in fact Black or Mulato.

In terms of how the fictional narrative was constructed, Isaura’s archenemy, Rosa, (extraordinary Afro-Brazilian actress Léa Garcia) was used as the evil antithesis of everything noble, good, and pure that Isaura represented. Rosa is presented as a “dark” soul, opposing Isaura, who is “untainted.” In that regard, the weight of Slavery’s unfairness and unjust system is measured against the visible fact Isaura is white.

Showing there were also white slaves in Brazil is not the problem. The issue is to use prime time TV to talk about slavery (for the first time) through the improbable story of a white slave who, in a Hollywood happy ending, is set free and marries a good looking blue eyed abolitionist “fazendeiro.”

Paula Halperin, SUNY Purchase

Thank you for this piece Greg. The telenovela was extremely popular in Ghana when I was growing up. Viewers (at least my family and I) identified with Isaura and wished Rosa all the ill in the world. Representation is indeed a powerful thing.

Do you know where I can get a copy of the telenovela today? I’ve wanted to re-watch it with a more critical eye for a while now and even contacted a distribution company with no success. Thanks!

Rede Globo released a DVD with the most important episodes last year to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the network.

Thank you Paula. I’ll see if I can track down a copy.